A motorcycle is a machine designed to transport us. We all know it can transport us not just to physical places, but also to a different (and usually, but not always, better) emotional state. It can’t actually transport us in time, but I have found that sometimes it can transport me to a place where I can see the past with a new and more insightful perspective.

What, you might reasonably ask, am I talking about? I’ll explain.

Over the years I’ve written hundreds of motorcycle articles for print (mostly for American Motorcyclist magazine, when I worked at the AMA) and online publications (mostly Common Tread at RevZilla, where I’ve been managing Editor the last 10 years). Some of those stories were travel pieces, especially at American Motorcyclist, where at least once or twice a year I would get to plan a trip to some worthy destination and write a feature article about it. That’s how I got to take some memorable “work” trips to places like Big Bend National Park and the heart of the Pacific Coast Highway, in addition to some special rides on my own time and dime, such as the Going to the Sun Road in Glacier National Park with my wife for our 10th wedding anniversary and a mid-winter escape deep into Mexico, stories that made it into my book.

Several times, when writing about those trips, I’d add, almost without seriously thinking about it, a line saying that I’d like to come back some day. For example, in my article about riding through Big Bend, I mentioned that it would be interesting to return on a dual-sport motorcycle, instead of the Harley-Davidson Road King I was riding at the time, so I could have an entirely different experience exploring the more rugged areas of that huge, empty, dramatic landscape on two wheels. Of course the more than 2,000 miles between my home and Big Bend make riding a dual-sport there an undertaking that is not casually dashed off on a weekend on short planning.

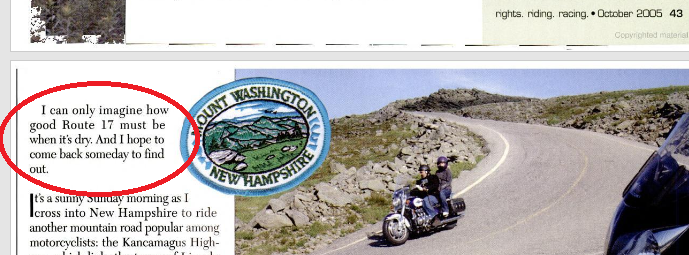

The article from the October 2005 issue of American Motorcyclist magazine in which I mention the idea of returning some day.

Recently, though, I did revisit one of those places I said in a past story that I’d like to return to. In 2005, I decided to write an article about a motorcycle trip measured not so much in the miles traveled across the surface of the Earth, but rather the distance traveled in elevation. I called it Vertical Touring and I rode a Suzuki V-Strom 650 around New England, charting the differences as I rode from sea level in Gloucester, Massachusetts, to Mount Greylock, the highest point in Massachusetts, then on through Vermont and New Hampshire and eventually reaching the most dramatic New England heights, the peak of Mount Washington, a mountain jutting up into the jet stream where some extreme weather occurs. Along the way, I was traveling north on Vermont Route 100, a famously scenic New England byway, when I stopped to help a fellow rider stuck alongside the road, trying to get his vintage Honda to run. Eventually it did, and he repaid my token help with some local knowledge, suggesting that I detour off 100 and “shoot the gaps,” meaning ride across the ridges on Lincoln Gap and Appalachian Gap. Which I did. In a steady rainfall, unfortunately. The hairpin turns and snaking curves of Vermont Route 17 became one of those spots I pondered visiting again, preferably when the pavement was drier.

In 2005, I had no idea that 19 years later I’d be living at the base of Mount Greylock, having the luxury of being able to use that scenic overlook as a quick, lunch-break escape on days when working at home starts to feel claustrophobic. And that also means that when a cool and sunny August Saturday rolled around, it was a simple and enticing matter to revisit Appalachian Gap for real.

The views along Vermont Route 100 are just as pleasant as they were 19 years ago, when I first visited.

The ride north on 100 was just as pleasant on my Honda VFR800 Interceptor as it was years ago on the V-Strom, but I also remembered why I was happy to get a detour recommendation from that local rider. Vermont 100’s scenic byway reputation comes more from its suitability for cruising along in a car than enjoying a brisk motorcycle ride. Route 17 over Appalachian Gap, however, is probably viewed by car drivers who are not true enthusiasts as more of an impediment than an attraction. Being able to bank through turns makes all the difference, making Appalachian Gap an entertaining challenge on two wheels, a potential recipe for car sickness on four.

What did I learn from the perspective of 19 years later? For one, that little stretch of two-lane was smaller than I remember, meaning the ride from the valley on one side to the valley on the opposite side of the ridge was a shorter one than I remember. Doesn’t everything loom larger in memory than it really is?

I also noticed the rider has changed a little in 19 years. Not totally. I still enjoyed running a brisk pace through App Gap’s hairpins and sweepers. But I also enjoyed the route home that I chose nearly at random, riding south and bouncing back and forth across the New York-Vermont border through gently rolling farmland. As I wrote in the chapter of my book about my long-ago trip to Mexico, I often enjoy going places where no one else goes just as much as I enjoy visiting those famous sights, such as California’s Highway One. I’ll go almost anywhere new to me, once. The change is a small shift in the balance, perhaps, that comes with age. A little less need to attack the curves, a little more interest in just seeing what’s around the corner.

The road across Appalachian Gap attracts riders, hikers, and others on a nice August Saturday. I shared space at the overlook with this group of mostly cruiser riders, passed other riders in pairs and groups of three, and one solo rider on a Ducati Hypermotard.

I remember one long-ago time when riding a motorcycle through a previously visited landscape gave me a strong sense of how my life had changed. The first part of that story dates to the days when I had just graduated from college in Ohio and moved to upstate New York to start my first job working as a newspaper reporter. One of the job requirements was having a car so I could get to assignments. Even if I wanted to try to fudge the rules and say my motorcycle counted, there was no way I could reliably get to an assignment on the Suzuki I owned in college when a Hudson Valley snowstorm was raging. I had to sell the motorcycle to fund the purchase of a used car, which led to a rare dark period in my adult life when I didn’t own a motorcycle.

During that time, I made trips from New York to West Virginia to visit family now and then, driving my used-up car. The most unpleasantly memorable trip began on Christmas Eve. I stopped for gas near Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and after filling up, the car wouldn’t start. The battery was fine, but no crank. I later learned the mounting bolts on the starter motor had loosened and the rattling around had destroyed the starter. But that day, on Christmas Eve, there was no hope of finding anyone to diagnose or fix the problem. Or the next day, obviously.

About 20 years later, after living in Florida, Costa Rica, and Puerto Rico, I was back in Ohio, working at the AMA. We needed to return a BMW R 1150 RT loaner bike to BMW headquarters in New Jersey and I concocted a way to get a story out of the trip as I returned it. I was riding the smooth and comfy BMW, a motorcycle more expensive than any of the used cars I’d owned in those earlier days, on the familiar stretch of I-68 through western Maryland when the strong feeling of “I’ve been here before” washed over me. Accompanied by a stronger feeling of “This is very different. And better.”

I pondered how things had changed in 20 years. Instead of hoping to nurse a crappy old car across those scenic mountains, a car that disappointed even more because it represented my lack of a motorcycle, I was riding someone else’s new sport-touring machine and getting paid to do it, whirring along under boxer power with not a care in the world. I felt a sense of satisfaction and gratitude that I still remember today on an otherwise unremarkable ride on a four-lane divided highway that would have been forgotten.

Motorcycles are machines built to transport us. Sometimes to a place where the view of the past is enlightening.