When the weather is right, there’s no more spectacular place for a motorbike race than the Phillip Island Grand Prix Circuit in Australia. Chaz Davies cuts laps in practice. Ducati photo.

This is usually one of my happiest weekends all winter: late February brings the first world championship motorcycle road race of the year as World Superbikes take over the beautiful Phillip Island Grand Prix Circuit in Australia. Each of the last few years, however, my anticipation has declined just slightly, and that’s the case again in 2018.

We’re not there yet, but I fear that a series I used to enjoy perhaps more than any other is slipping too far from pure sport and edging closer to spectacle. Will this be the year the FIM Motul Superbike World Championship title is determined not by the racers but by the people who make the rules? It’s possible, because of some changes made this off-season.

There are a few tensions at work. First, since Dorna gained control of both WSBK and MotoGP, it has taken steps to make it clear that MotoGP is the big show, the top level, and WSBK, while still a world championship, is secondary. There was a time when it was not so clear cut, back when the GP series was racing 500 cc two-strokes (interesting and impressive, sure, but hard for an everyday rider like me to relate to) while WSBK pitted production-based motorcycles against each other, with 750 cc four-cylinders against liter V-twins. The story lines were more interesting in WSBK. It provided race-tested evidence of the kind of stuff we riders talk about. What’s better, a twin or a four? It gave local riders a chance for a wild-card ride and a shot at international attention when the series came to their country, because everyone was racing Superbikes.

Plus, it had the personalities to match, such as Carl Fogarty. There was a time when people talked about World Superbike eclipsing GP racing, and it wasn’t wild conjecture. Personally, I don’t think I’ve ever enjoyed following a title chase more than watching the incredible comeback by Colin Edwards on a Honda from 58 points down to catch Troy Bayliss on a Ducati to win the 2002 Superbike World Championship. That classic battle ended at an amazing title-deciding race at Imola, with both riders throwing passes at each other in the final laps.

The switch by GP racing to four-strokes shifted the balance, as riders and manufacturers alike were more interested in MotoGP than Superbikes, and Dorna’s concerted efforts to emphasize MotoGP’s superiority settled the matter. But now, I think there’s a bigger threat to World Superbike, and it comes from the other tension at work in racing today.

Two U.S. riders will be racing in World Superbike this year. Jake Gagne was called up from MotoAmerica to ride for the Red Bull Honda team, replacing the late Nicky Hayden. P.J. Jacobsen will ride for the TripleM Honda team. Red Bull Honda photo.

Is it a sport or a show?

This tension is not limited to WSBK. Some years ago, it became consensus that racing series had to focus on putting on a good show for the fans. That’s a relatively new development. Unless you’ve studied racing history, you probably don’t realize that 50 years ago the average margin of victory in grand prix racing was around two minutes. In 1968, Giacomo Agostini won all 10 Grand Prix races, winning nine of them by more than a minute.

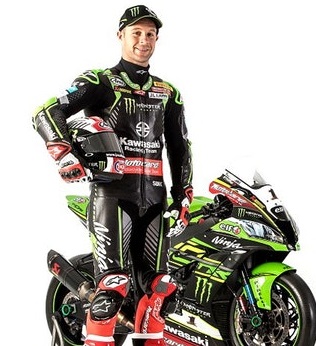

That just won’t do today, and while nobody’s winning a WSBK race by a minute, Dorna is not happy with the outcomes. In the past two years, every race has been won by either the Kawasaki Racing Team or Aruba.it Racing team, except for Nicky Hayden’s one amazing win in the rain in Malaysia in 2016. Jonathan Rea, on the Kawasaki ZX-10R, became the first man to win three consecutive WSBK titles last year, and he won by dominating margins of 132, 51 and 153 points. With six more race wins, Rea will break Fogarty’s career record of 59 wins and a fourth title will match Fogarty’s record for championships.

Jonathan Rea and his Kawasaki have dominated three years straight. If the other riders can’t beat him, the WSBK rules makers might just do it themselves. Kawasaki Racing Team photo.

Dorna isn’t so much concerned about the record books, but the dominance by two teams, and mostly by one rider, is “hurting the show,” to paraphrase the terminology that’s common in racing these days. If the other teams can’t beat Rea, Kawasaki and Ducati, the rules makers just may do it themselves.

For 2018, the WSBK rule book imposes rev limiters on the bikes, but the limits are not the same for all teams. Aprilia, BMW, MV Agusta, Suzuki and Yamaha Superbikes will be allowed to rev to 14,700 rpm if they want. Hondas are limited to 14,300 rpm and Kawasakis are limited to 14,100. The Ducati Panigale V-twin, in its last year before it is replaced by Ducati’s V-four, is capped at 12,400 rpm.

After every three rounds, the performance and results of the teams will be evaluated based on a formula that hasn’t been revealed in detail. Basically, if Kawasaki is winning too many races, setting too many fastest laps or qualifying on the pole too often in the eyes of the rules makers, the maximum rev limit for all the Kawasakis on the grid can be reduced by 250 rpm. Theoretically, the series could keep squeezing the power every three rounds until the desired result is achieved.

Two other new measures for 2018 are also aimed at tightening the field. One is “concession points.” Points are awarded for podium finishes and teams that fall too far behind will be allowed to introduce upgraded engine parts. Teams with a lot of podium finishes will have to keep using the same spec parts they started the season with. Additionally, the costs of certain parts, such as cylinder heads, are capped and those parts must be made available to any team. This gives privateer teams the chance to use the same spec parts as the ones on the factory race bikes.

These new rules — especially the rev limits — are the most extreme effort yet to change the results. In the past, WSBK rules used air restrictors to try to balance the performance between V-twins and four-cylinder race bikes, but this is different in a fundamental way. Those rules were aimed at leveling the playing field. These are aimed at evening up the results. This is a shift toward a focus on the “show” and away from the “sport” aspect of racing.

I say that because this is something we don’t see other professional sports doing. If the Golden State Warriors go on a winning streak, the NBA does not decree that in the second half of the season their basketball rim will be raised to 11 feet instead of 10. The rules aren’t changed mid-season to achieve a different result.

Last year, I thought the race-two grid shuffle was a bad idea but in the end it didn’t really make much difference. Maybe once again I’m worried about nothing. Maybe this year the rules makers will take a measured approach and let the best team win, instead of punishing the winners until they no longer win. We will see.

All I know for sure right now is that the prospect of a potentially rigged series makes me a little less excited about what should be one of my most anticipated weekends of the winter.