40-year-old gauges that aren’t faded by the sun and show zero miles are evidence of Chuck Floyd’s approach to building the motorcycle of his childhood.

Remember the excitement of your first motorcycle? Remember the feeling of freedom it gave you, even if you were just a kid putting around in the dirt in a vacant lot?

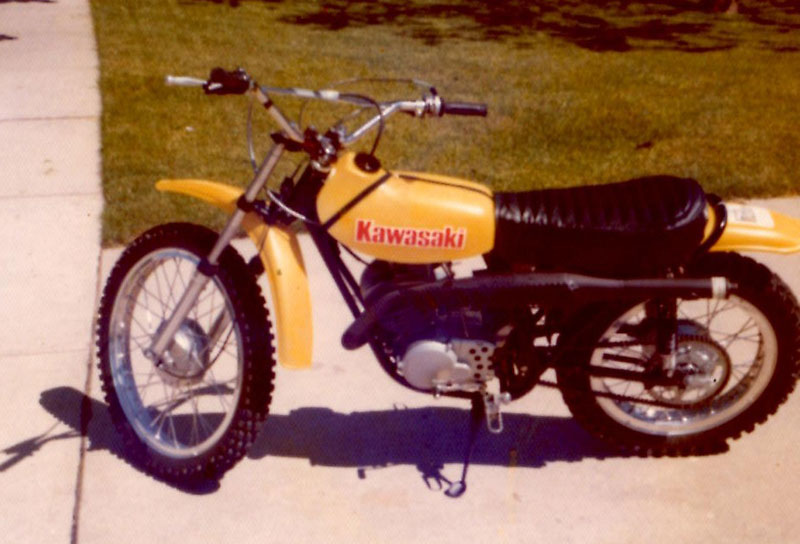

Chuck Floyd remembers more vividly than most. And he’s acting on that memory more strongly than most. Lots of people in midlife or retirement years buy a motorcycle they owned in their youth, but Floyd didn’t settle for restoring a 1972 Kawasaki F6 enduro like the one that changed his world as a 14-year-old boy growing up in Lansing, Michigan. Instead, he embarked on a multi-year project, now more than 95 percent complete, of building a 1972 F6 almost completely from new old stock (NOS) parts.

That’s right, sometime this year Chuck Floyd is going to have a 1972 Kawasaki F6 that’s brand new in nearly every way: no miles on the engine or transmission, every part as pristine as the day it came out of the Kawasaki box. Because each part did just come out of the box.

“Every nut and bolt and washer on that bike is Kawasaki. It’s going to be as close to a brand new 1972 motorcycle as you can build,” said Floyd, who recently retired and now lives in Whitehall, Michigan. “I’m sure it won’t have half the value I have into it, but it makes me very happy.”

And that’s the key to this project, which so far has spanned three years and consumed roughly $10,000. It’s all about rekindling the excitement he felt as a 14-year-old boy buying his first “real” motorcycle after the minibikes of his childhood.

“When you’re 14 and you’ve just been handed the keys to a new motorcycle, it’s like getting a new Porsche 911 Turbo,” Floyd said.

A Kawasaki ad from 1972 shows the F6 in original form.

To buy that 1972 F6, Floyd saved the money he earned delivering newspapers and sold his minibike. His father took him to the Kawasaki dealer, where he expected to buy a 100cc model. But his father, who never rode a motorcycle himself, looked at his lanky son, looked at the 100cc enduro and the larger 125cc model, and asked his son if the larger motorcycle wouldn’t be a better choice. Naturally, young Chuck jumped at the opening and his father kicked in the difference to buy the bigger bike.

That summer, Floyd and his buddies rode their dirtbikes every spare moment, exploring trails and dirt roads and getting their first taste of the feeling of freedom and independence.

“I’ve had lots of motorcycles in my life, but that one was special,” he said.

Within a couple of years, however, Floyd and his buddies began doing more racing, mostly hare scrambles and enduros. His F6 couldn’t compete with the lighter motocross bikes that were starting to come out of the Japanese factories, so he started stripping parts off his F6 to make it a racebike. He convinced his welder teacher at his junior high school to let him borrow the school shop’s welding torch to cut off no-longer-needed brackets and reduce weight. Those unused parts, such as lights, the cylinder and head that were replaced to bump displacement to 175cc, and other bits, were dumped into boxes. Not much later, the converted racebike was sold to finance other vehicles, with both two wheels and four, as Floyd moved through his teen years. He kept those boxes of F6 parts for more than 20 years, however, until his wife asked him, during a move in 1997, why he still had them. Since he couldn’t come up with a good reason, he dumped them.

This photo shows Floyd’s boyhood F6 after he modified it for racing by stripping parts, mounting a 21-inch front wheel and making other changes.

“I actually just threw them in the trash,” Floyd said. “Then regretted that day forever.”

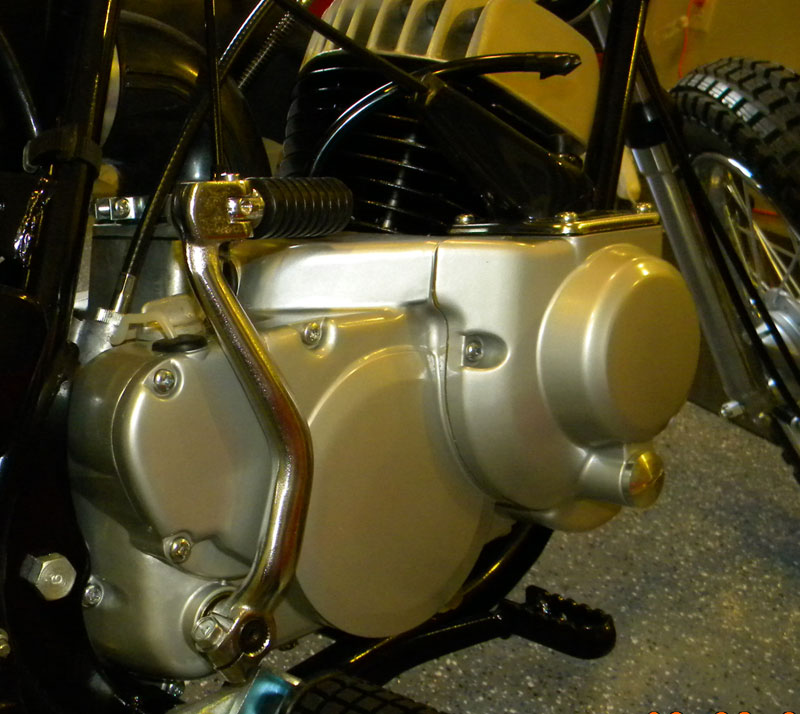

That’s because as soon as he retired from his career as an executive for an employee benefits management firm, he decided to rebuild the motorcycle of his teen years. The idea came to him when some internet research revealed that many NOS parts were still available, even for a 40-year-old dirtbike. One major source was Johnny’s Vintage Motorcycle Company in Wadsworth, Ohio, which had bought up stocks of old Kawasaki parts whenever available. Through Johnny’s, Floyd assembled all the parts needed to build the engine, and then Hilo Ito, a Japanese mechanic who works at Johnny’s, assembled it for him.

Floyd is still undecided whether this pristine engine will ever run.

Floyd also sourced parts from eBay, through his connections in the Vintage Japanese Motorcycle Club, at swap meets, and he bought some directly from Kawasaki. But finding certain NOS parts was impossible. For example, Floyd started with a used frame, which he had stripped and painted. And everyone knows that a handlebar on an off-road motorcycle is a perishable item. He finally had to have a used handlebar straightened by a shop in Illinois and then he sent it to another shop in Kentucky to have it plated. He’s still looking for a NOS gas tank, too, but he has a used one that he’ll restore, if he can’t find a new one.

The 1972 F6 is coming together in Floyd’s garage. Notice the carefully labeled and organized parts bins in the background.

Not surprisingly, none of this is cheap.

“You can end up paying $20 for a bolt,” he said. “I realized early on this was going to be a very expensive proposition, but I couldn’t stop.”

As he gathered the hundreds of parts he needed, Floyd had to keep the project meticulously organized. Each part he obtained was checked off in the original Kawasaki parts manual that he called “my Bible” and was labeled and placed in a plastic bin corresponding to a section of the manual. Because of his detailed records, Floyd can tell you that he bought 1,438 separate parts for the project, from individual nuts and bolts and gaskets to transmission gears. Of those, 93.6 percent were NOS, while 4.5 percent were new Kawasaki parts. That’s right, you can still get new brake shoes and speedometer cables for a 1972 F6. The remaining parts, less than 2 percent of the total, were restored or reproduction pieces.

While Floyd’s F6 still isn’t totally assembled, he did put a battery in it so he could turn the key and enjoy seeing the lights come to life. He hasn’t yet answered the big question: Will he ever ride it? Or will he keep his new 40-year-old F6 in brand-new condition? He’s of mixed mind on that one.

With all the hours and dollars spent on the project, what’s the motivation that has kept him going?

“Remember that excitement when you got your driver’s license? This bike does that for me,” he explained. “Every time I touch that bike it takes me right back to when I was 14. Nothing else quite gets me excited like that.”

It’s like 1972 all over again.

2013 update: The F6 finished

When he finally considered his labor of love to be complete, Floyd sent me this photo of his brand new 40-year-old F6.

The F6, built part by part.

I had to ask how he finally came down on the question that I know would be the hardest one for me to answer, if I were in his place: Will he ever start or ride his factory-new motorcycle?

“I haven’t started it and I don’t think I ever will,” Floyd says. “It’s too special … at least to me, anyway.”

Originally published in Accelerate magazine.